Jan and Mike Riter, Subaru/IMBA Trail Care Crew

Every person engaged in trail building and maintenance should understand the interrelated concepts of bench cuts and fill slopes, outslope, fall-line versus contour routes, and maintenance by deberming.

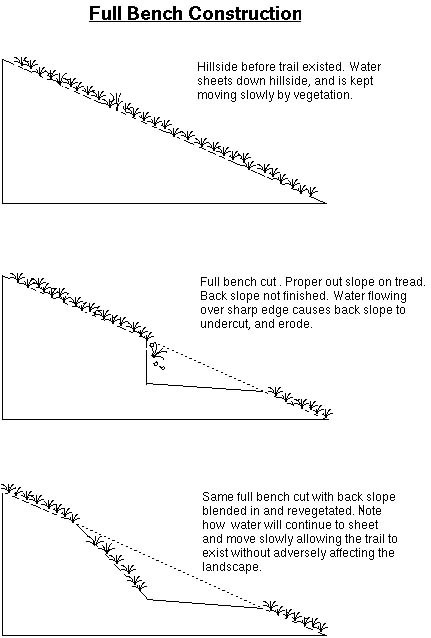

A bench cut is the result of cutting a section of tread across the side of a hill. If you look at the side profile of this cut it looks like a bench, hence the name. The two basic designs are known as "full bench" and "partial bench." Full bench construction means that the full width of the tread is cut into the side of a hill. The entire tread is dug down to compacted mineral soil. Viewed in cross-section, the tread angles slightly downhill at 3-5%. This is known as outslope. A partial or balanced bench means that part of the hill is cut away and the soil that has been removed is placed at the lower edge of the trail to try to establish the desired width. This is known as a fill slope.

We have yet to run into an area that did not require a full bench cut.

Full bench design avoids problems inherent in partial bench cuts. Partial bench often requires problematic cribbing (the act of putting logs or rocks on the downhill edge of the trail) to hold the fill soil that is added to the edge of the trail. The fill soil is soft and uncompacted, often forming a berm, which will cause water to flow down the trail rather than across it. The end result: Your new or reconditioned trail ends up being the poster child for erosion damage. And if a user finds their way onto this soft edge, they can lose their balance and end up off the trail, or push the soft dirt down the side slope causing the tread to terrace or become uneven.

Bench cut and fill relates directly to trail layout. We always recommend building trails that contour across a slope, climbing and descending gradually, rather than running directly up and down the fall line. (The fall line is the most direct route downhill from any particular point.)

Water generally runs down the fall line, and fall line trails provide a conduit to move a lot of water down a hill. Water flowing down a trail will build velocity and will quickly erode deep ruts into the tread. Fall line constructed trails erode at a terribly fast rate, are nearly impossible to maintain, and fuel the fires of people who are looking to ban bikes from trails. Too many unskilled riders skid or ride out of control on fall line trails.

On the other hand, contour trail are curvy, fun to ride, easier to maintain, yet still provide significant challenge for even the most skilled riders. Contour trails should be built with outslope so water will sheet across the trail and continue down the hill, rather than diverting into the trail tread and causing erosion. If a drainage problem does develop on a contour, full bench trail, it can be dealt with easily and effectively.

Contour, full bench, and gradual trails will require less maintenance and fewer water diversion dips than fall-line, partial bench, or steep trails.

Some time after a trail tread has been properly cut in and outsloped, the tread will settle from compaction. This is normal. However, the lower edge of the tread will not compress as much as the center, creating a berm. Berms can also form from erosion. Fortunately the cure is simple and very effective. Using simple hand tools (McLeod, Pulaski, adz hoe, pick, etc.), remove the berm to create outslope, being careful not to disturb the already compacted center of the trail any more than necessary. Varying by soil types and climate, many trail segments will require another deberming five or more years later. This is perhaps the most common maintenance needed on trails, but also the easiest and most effective.

We have been asked by folks in areas that have a lot of sand if it is a good idea to build a bench trail, as opposed to just raking back the surface vegetation and letting the users establish the tread. It is especially important to bench and outslope the trails in these areas. If not, the thin layer of topsoil will quickly punch through and cause the tread to become cup shaped, channeling water down the trail.

In sandy areas, it helps to add something to harden the tread surface and make it sustainable. If there is a layer of compactible soil on the surface and sand or glacial till (the debris left when a glacier retreats) underneath, then the upper layer can be removed and set aside, then mixed with the sand for the top of the tread. If there is no compactible layer, then other hardening techniques must be applied (see ITN Trail Tips, July-August, 1998).